Oral Contraceptives’ Effect on Cortisol

The release of birth control in the 1960s brought sexual liberation to women- a chance to live and pursue career goals and have sex without the fear of pregnancy. However, with the exciting benefits of this long-awaited advancement, it was easy to forget the dangers of ingesting synthetic hormones on a daily basis- synthetic hormones that do not discriminate when it comes to receptor-binding. Estrogen and progesterone bind to cell receptors throughout our entire body, including receptors on our brains. Therefore, synthetic hormones have a broader biological effect than merely preventing pregnancy. A medication’s side effects usually result from its inability to target receptors in only one specific location. Think of the prevalent and well-known risks/side effects of anabolic steroids (synthetic testosterone). Yet, despite millions of women being prescribed oral contraceptives (synthetic estrogen and progesterone), hormonal birth control’s risks are rarely discussed.

One risk, noted in the 1990s but only coming into the limelight in recent years, is oral contraceptives’ effect on cortisol, a steroid hormone known for its role in stress. Cortisol gets a bad rep because chronically high cortisol is linked to insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, hypertension, and dyslipidemia.³ Recent research is finding significant differences in cortisol levels in naturally-cycling women versus women on the pill (as well as women on other forms of hormonal birth control; however, those studies are not cited here).¹

An Average Menstrual Cycle vs Oral Contraceptives

To better understand the hormonal patterns of a woman on the pill, it helps to first understand a “natural” menstrual cycle.

The first day of your period is considered “day 1” of the menstrual cycle. Estrogen and progesterone are both low. After the uterine lining is shed and the period comes to an end, estrogen begins increasing in preparation for ovulation. This is the follicular phase, in which the egg that is going to be released during ovulation is maturing. With increasing estrogen, women have decreased appetite, increased libido, and increased perceived attractiveness.¹ Studies have found that women (and their scents) are considered more attractive near ovulation when fertilization is possible; this is a tribute to our bodies’ subconscious and innate instinct for reproduction.¹

Ovulation, which is the release of an egg from an ovary, occurs around day 14 of the menstrual cycle. In the days following ovulation, the body begins to prepare for the potential implantation of a fertilized egg, and it does so by increasing progesterone (mirrored by a slight increase in estrogen). Progesterone increases GABA synthesis (an inhibitory neurotransmitter known for its relaxing properties), increases appetite, and decreases sex drive.¹ In this part of the cycle, known as the luteal phase, studies have found heterosexual women are more likely to prioritize men with long-term potential rather than “sexy men” with symmetrical faces as they do during the follicular phase.¹ (It should be noted that many of these studies were done on primarily heterosexual women, and more research on LGTBQ+ individuals is needed.) When the body realizes pregnancy has not occurred, there is a rapid drop in progesterone (and estrogen), which is thought to contribute to PMS symptoms, and the uterine lining is shed once again, to start the cycle over and prepare for another potential pregnancy the following month. Women’s bodies are truly amazing.

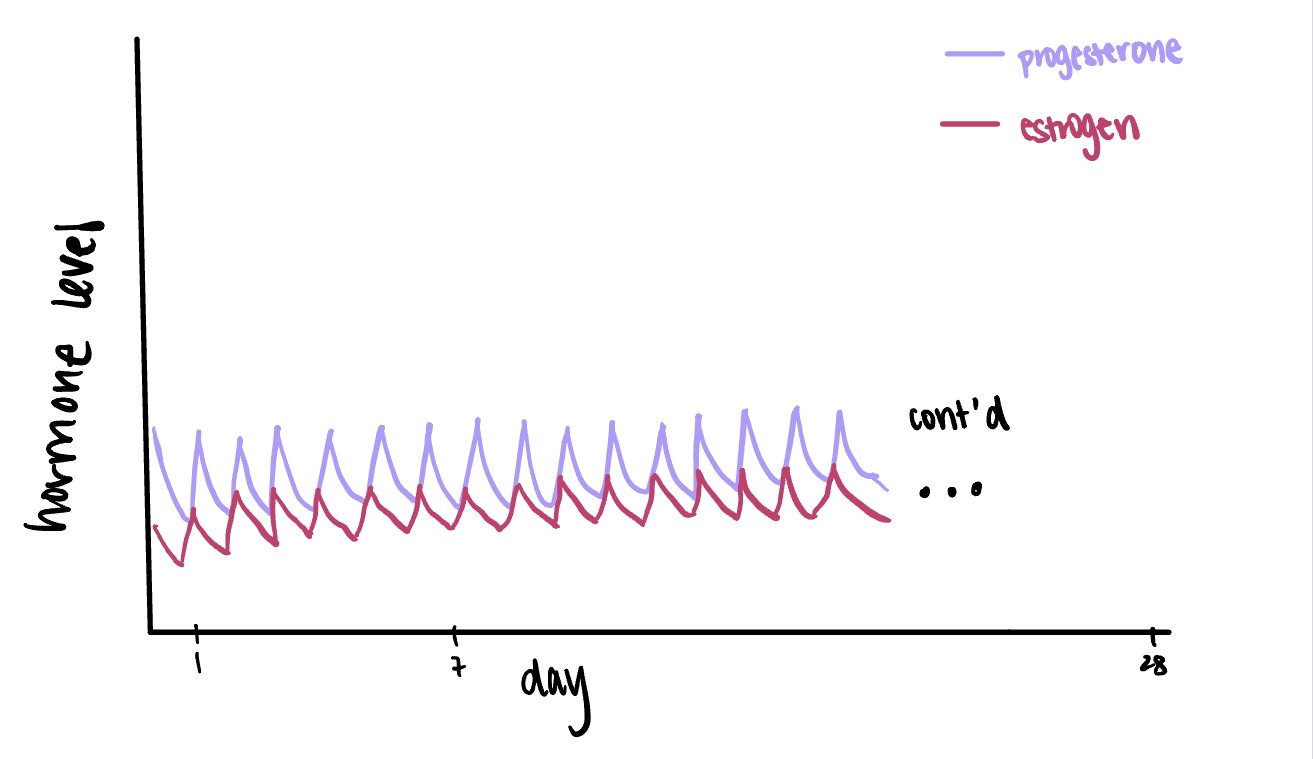

When a woman is on the combination pill, there is daily administration of estrogen (ethinyl estradiol) and a progestin (either a first, second, third, or fourth generation progestin). This exogenous administration seems to mimic the luteal phase of a natural menstrual cycle. Hence, the weight gain associated with some oral contraceptives might be an indirect result of progesterone’s tendency to increase appetite. Below are figures displaying 1) estrogen and progesterone levels throughout a 28-cycle of a natural menstrual cycle and 2) estrogen and progestin levels on oral contraceptives.

Figure 1. Hormone Levels Throughout Average 28-Day Menstrual Cycle.

Figure 2. Hormone Levels When on Combination Pill Oral Contraceptive.

Cortisol Levels & Stress Response

Although both naturally-cycling women and women on the pill respond to stress with activation of the sympathetic nervous system (norepinephrine and epinephrine), studies are reporting that women on the pill do not experience the same increase in cortisol that naturally-cycling women (and most humans) do in the presence of acute stress. Rather, they have a blunted, and sometimes even nonexistent, response.¹ This is interesting because women on the pill simultaneously have higher levels of total cortisol (both active and inactive, CBG-bound forms).¹ The cortisol response pattern (elevated total levels, blunted stress response) is not only a sign of a dysregulated HPA axis, but it also matches cortisol patterns of trauma victims and those experiencing PTSD.¹ Other biological markers that are mirrored in both women on the pill and those who have experienced trauma include elevated triglycerides, increased expression of genes involved in glucocorticoid signaling, and smaller hippocampal volumes.² Further studies are needed to determine if these changes remain after a women stops taking oral contraceptives. The indication that oral contraceptives may reduce hippocampal volume is also incredibly relevant when discussing memory consolidation and the increased risk of Alzheimer’s in women compared to men.

Why do we care about cortisol?

Cortisol has been a hot topic in recent years in the medical world, and with good reason. Cortisol is instrumental in energy balance and memory consolidation. Cortisol elevation triggers increased lipolysis, increased gluconeogenesis, and increased protein breakdown in order to increase blood substrates for energy production and use (i.e. blood glucose levels, plasma fatty acids, and plasma amino acids). In a “survival”, fight-or-flight situation, having enough blood glucose to run away is essential. However, in the long-term, this is detrimental to immune functioning and digestion, as well as cardiovascular health. In other words, acute cortisol spikes are evolutionary adaptive, but chronic cortisol elevation is metabolically unhealthy. Women on the pill are lacking acute cortisol spikes, yet have chronically high levels of cortisol.

(For more information on the biochemical details of cortisol, check back for future blog posts.)

Now what?

This isn’t to say the long list of pros of hormonal birth control do not outweigh the cons. But, this research should not go unnoticed or undiscussed, considering millions of women- especially young women whose brains are still developing - are prescribed birth control, unaware of its side effects. As a naturopathic medical student, nonmaleficence and patient autonomy are two of my highest priorities; women should be fully educated on the current research on oral contraceptives, so they can make the best decision for themselves regarding their birth control use.

The pill offers a range of benefits, and it should be noted that an oral contraceptive’s effects can vary greatly between individuals, depending on dose, progestin, etc. However, my personal recommendation would be to encourage physicians to address the root cause of hormonal imbalances, rather than suppress natural hormone production, for women taking birth control for reasons other than pregnancy prevention.

References

1. Hill S. This is your brain on birth control: The surprising science of women, hormones, and the law of unintended consequences. New York, NY: Avery Publishing Group; 2019.

2. Hertel J, König J, Homuth G, Van der Auwera S, Wittfeld K, Pietzner M, et al. Evidence for stress-like alterations in the HPA-axis in women taking oral contraceptives. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2023 Jun 1];7(1):1–14. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-13927-7

3. Whitworth JA, Williamson PM, Mangos G, Kelly JJ. Cardiovascular consequences of cortisol excess. Vasc Health Risk Manag [Internet]. 2005;1(4):291–9. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/vhrm.2005.1.4.291